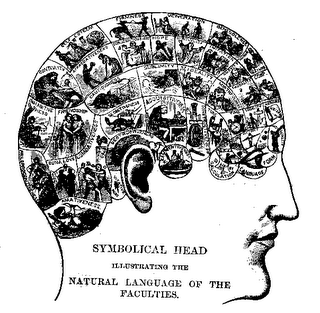

February 4: [Sunday] All here to dinner except Mat. We had quite a lively day. Some poor woman in the Quarter lost her baby today. Two children have died in the last 3 days. After the distraction of the visitors, I busied myself in my Phrenological pursuits.

Mary Virginia Montgomery was one of four children born to Mary Lewis and Benjamin Montgomery. Both the Lewises, the Montgomerys, and their children were former slaves of Joseph Davis, brother of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The plantations known as Hurricane and Brierfield, were located near Vicksburg along the Mississippi River. By the time Mary Virginia wrote in her diary, her parents actually owned both Davis plantations and a third plantation known as Ursino. In 1872, the Montgomerys were some of the wealthiest planters, black or white, in the South.

But MV, as she was affectionately known, spent some 14 years as the slave of Joseph Davis growing up at Hurricane. Her father, Benjamin Montgomery, had been sold down river as a young man. Joseph Davis purchased him and brought him to Hurricane. Ben Montgomery immediately ran away. When I asked why he ran, Montgomery expressed that he did not want to be a slave. During the course of the questioning, Davis realized that Ben Montgomery was no ordinary slave. He was quite brilliant and literate, having learned to read and write from his former captor.

Hurricane was unlike any of the other plantations in the area. Some time prior to Ben Montgomery coming to Hurricane, Davis had taken a stage coach ride with utopian idealist and social reformer Robert Owen. Owen espoused that if you treat your workers with some degree of dignity and respect, they would be more productive. The key words here are "productive" and "production." White men often operated under the guise of benevolence and honor in the antebellum South, wearing patriarchy like an Easter Sunday dress. All their insecurities, weaknesses and homophopic tendencies were interwoven within the garment's silken threads, carefully stitched and displayed under the banner of honor.

Patriarchy, productivity, curiosity and science caused Joseph Davis to sit up and listen to Scottish reformer Robert Owen and to institute some of Owen's ideas on his plantation. For instance, many slaves were allowed to learn to read. There were also courts in which the enslaved played a role in determining the fate of their peers. The enslaved captives were also given medical care and housing well above what was allowed on nearby plantations.

In a few short years after being sold down river, Ben Montgomery reached a mutual agreement with Davis to open a mercantile business. Montgomery become so successful at this venture that he actually paid Davis his wife's wages so that she could stay at home with their children. Ben was deeply concerned for the education of his children. At one point, he hired a tutor for Mary and her siblings. When Davis found out, he sent his own children to the class. Surrounding planters heard about the integrated "school" and protested. The school was summarily dissolved.

It was in this atmosphere that Mary Virginia was born--a female slave in Mississippi, whose father and mother, also slaves were allowed to accumulate some degree of wealth. While this may appear to be advantageous, we must ask how might their social status affect they way that they were treated and their attitude towards others. There is something troubling about MV's passage in her diary, especially when she comments on the "distraction" of the deaths of the two babies in the quarters.

It appears that MV has much on her plate, she has been a slave, yet not a slave. She is educated and isolated. She is pretentious, yet realistic being constantly reminded by the flooding waters of the Mississippi River and the weakened levees that her father fights to repair and adjust on a daily balance that life is delicate at best. For an un*slave, however, imagination and fantasy are rich in abundance. The question is, 'how do we get there' and when we arrive, what will we find?