I Like It Like That

I like this idea of self-portraits.

> Tracey

Tracey wrote this to me a week or so ago and I have not had a chance to respond. Why do you think self portraits are a good idea? Do you like the idea of performance that is inherent in self-portraiture or do you feel that only you can best express who you really are?

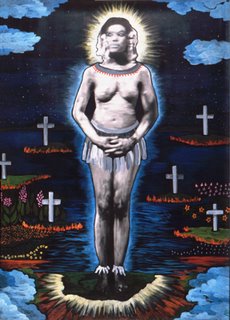

I like both the performative and voyeurist aspects of self-portraiture. There is a certain degree of scandal that is involved in removing one's clothing and posing as I did in the image from the last post. The image was from a series entitled The Annotated Topsy. This series examined the character Topsy from Harriett Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. In that series I used the universal concept of opposites (night and day, black and white, yin and yang) to tell the story of Topsy's psychological battle for goodness. I use Stowe's work to enter into my own imaginal space by continuing the story where Stowe left off. Stowe literally writes Topsy out of the novel after Topsy is taken to a northern free state. I cover Topsy's experience in the north and rejoin Stowe when she reintroduces the character at the end of the book.

In Stowe's novel, Topsy claimed that she was "wicked" although little Eva assured her that she was not. Topsy repeatedly promises to be good and repeatedly fails. My text explores abuse and neglect of slave children and why their attempts to be good might be doomed to failure. Topsy's quest for goodness is haunted not only by the physical abuse that she received as a child but also by her African ancestors who remind her constantly that she is black and is therefore considered not good by her European oppressors.

On that note, please go back to the last post and look at the work of others and how they use self-portraiture in their work. Is there anything that might resonate for you in their work? Look at the work critically and ask yourself questions? How does Carrie Mae Weems use language, storytelling and photography in her work? What about symbolism? Can the symbolic speak? If so, how? Can you realize your own symbolic language through visual imagery? We have already looked at the women's bodies on the raft and the language that their bodies impart. What other ways can you use your body in your own photography to signify defiance and protection? Might you become invisible? If so, how? Just a few questions to guide you along, but ultimately it will be your own questions that will guide you.

Good luck and thanks Tracey for your comment and for comments from other members.

The above photograph can be found at http://www.iath.virginia.edu/utc/onstage/films/kalemhp.html